Part I

Klaus Richter had traveled the world, documenting the lives of both the famous and the obscure. From the royal courts of Europe to the favelas in Rio de Janeiro to the war-torn village of Aleppo, there wasn’t a corner of the Earth that hadn’t been scrutinized and immortalized through his documentaries. He’d been at it for over thirty years, moving quickly from project to project, accumulating prizes and new opportunities. But for the past decade, to him at least, his work felt derivative and redundant. At a time when someone was always sticking their phones up to capture every moment of every day, it was hard to believe there were any stories left to tell —that is until Klaus Richter met his diplomat friend Emil Rossi at a bar in Lisbon.

Klaus and Emil grew up together and were rivals during their foundational years. They pushed each other the way good rivals do, and after they branched out into the world, they both found success in their chosen fields.

Emil raised his glass. “I’m happy to see you in person. It’s been how long?”

“I have no idea. Three, four years?” Klaus said.

They clinked glasses and took a swig.

“It has been longer,” Emil said.

“How have you been?” Klaus asked.

“The last month has been rough, I must confess,” Emil said.

“I’m sorry about Helene. I should’ve been there,” Klaus said.

“You were with us,” Emil said.

“The live feed doesn’t count. It’s not the same.”

“That’s how things are done these days.”

“I was stuck in Buenos Aires and—”

“She crossed the threshold peacefully.” Emil raised his hand and ordered two Porto tonics.

“I couldn’t watch the end,” Klaus said.

“Nobody did. I cut the feed before she departed,” Emil said. “But all endings are the same. How is the work?”

“It’s been better.”

“Congratulations on your last documentary, by the way. I read about the award,” Emil said.

“I don’t know. Nowadays, everyone seems to have a documentary in them.”

“Why are you complaining? I’ve spent my whole life working in the shadows while you’re operating under the spotlight.”

“You’ve had two documentaries made about you,” Klaus said.

“Both by film students.”

“Still, you are the kingmaker —the man behind those with real power.”

“I’ll be tossed to the curb soon, and nobody will remember me,” Emil said.

“I will be forgotten, too.”

“You must be drunk already.”

“I’m serious. The world is changing.”

“The world is always changing, so it can stay the same.”

“Look, as we speak, there’s a crew filming the bartender preparing our drinks,” Klaus said.

“What could be interesting about mixing Cosmopolitans?” Emil asked.

“And there’s a crew following that crew. They’re probably filming the ‘Making Of’ whatever documentary they’re doing on the bartender. Tomorrow, another crew will film the waiters. The day after, the dishwashers, and so on.”

“But your stuff is different. You tell stories about people who do not care to be found,” Emil said.

“We are close to reaching a point where every person on Earth has a documentary made about them. I’m not exaggerating.”

“Most of those films are unimaginative —mere copies of each other.”

“I don’t know. The AI is already pretty good at turning amateur footage into something that looks professional,” Klaus said.

“This is why I wanted to see you. I have your next project,” Emil said.

Emil told Klaus about a man without a story —no films, books, or songs— just a man hiding in the world's most remote and inhospitable corner. He was remarkable because he was genuinely anonymous and had a reason to be so. Emil promised this man’s story was one nobody else could tell.

“How do you know about this fellow?” Klaus asked.

“Helene. She was going to tell you, but you know.”

“Right. So what’s the angle?”

“Helene left this for you,” Emil handed Klaus a package. “Everything’s there.”

Part II

After flying from Lisbon to Oslo, Klaus took another flight to Tromsø, a city known as the Gateway to the Arctic. From there, he boarded a rusted cargo ship that doubled as the world’s worst cruise liner, crossing the frigid waters to Longyearbyen, the administrative center of Svalbard.

The journey was punishing, and Klaus often second-guessed his sense of direction even though there was no other way to go but North. Although Helene was the best researcher he had ever known and a close collaborator, he wondered if he was making the trip out of guilt or pure self-interest. Maybe he was allowing Helene to lead him one last time. After all, she knew him. The last time they talked, Klaus had called her before he left for Argentina, and they stayed up until the morning chatting about his mental block and his fear of getting old and irrelevant. Perhaps this was Helene’s way of helping a man whose creative well had dried out. He was going on belief alone —faith that Helene’s instincts were accurate and that the story was not as foolish as it sounded. As the cold ate at his bones and the wind howled relentlessly, Klaus pressed on, trying to convince himself that he was on the verge of reinventing his career as a documentarian.

The final leg of the journey was by snowmobile, piloted by a grizzled Norwegian guide who spoke only in grunts and monosyllables. As they tore across the tundra, Klaus thought of Helene's final note: “Although you have a gift for extracting stories from people, don’t push him. Remember that he’s hiding for a reason.”

Finally, they arrived at Ny-Ålesund. The village was little more than a collection of wooden houses huddled together against the cold. Beyond them, the Arctic Ocean stretched into infinity, the ice merging with the sky in a seamless, white horizon. Klaus dismounted the snowmobile and stared at the cabin. This was it —the Last Untold Story. He said goodbye to the guide, grabbed his equipment, and walked toward the cabin, the snow crunching beneath his boots with each step. He had no idea what he would find inside, but he hoped Helene was right and that whatever it was, it would be worth the adventure. That’s all this is, Klaus thought. Life is an adventure, and he immediately felt like an idiot for thinking in cliches. Is this what getting old was like?

Part III

It was a simple structure, weathered and worn, with smoke curling lazily from the chimney. He knocked on the door, half expecting no answer. But the door creaked open, and there he was.

“Come in,” the man said, his voice warm and inviting. “You must be freezing.”

Klaus stepped inside and was struck by the contrast between the man and his surroundings. The cabin was sparse, but the man was tall and robust, with a mane of red hair and bright green eyes. He looked like a figure from myth, a god in exile.

“I’ve been expecting you,” the man said, gesturing for Klaus to sit by the fire.

“Who told you I was coming?”

“It was only a matter of time before someone came looking,” the man said.

Klaus wasted no time. “Are you Julian Eldritch?”

The man searched a cabinet for something. “I suppose that’s the case.” He found a cup, served some coffee, then handed the cup to Klaus. He smiled and remained standing.

“Thank you,” Klaus took a sip. “It’s ice cold.”

“Is it?” Eldritch took the cup back and drank from it. He smacked his lips. “I’ll make some more then.”

“For someone who has been hiding, you don’t seem surprised to see me,” Klaus said.

Eldritch pulled a large wooden box from the corner and searched through it. “Hmm, I don’t know. Villagers are nosy,” He said.

“I’m not your neighbor,” Klaus said.

“Aren’t you?”

“I am Klaus Richter.”

Eldritch removed a few things from the box and placed them on the table. “I know I put the picture around here somewhere.”

“I’m a filmmaker. I’ve written, produced, and directed fifteen award-winning documentaries.”

“Fifteen, huh? That’s a good number. Is that your camera?” Eldritch pointed at the suitcase.

“I won’t use it if you don’t want me to. Normally, there’s a discovery process, interviews, calls, and such, but the nature of this story didn’t allow for any of it. I hope this is not a problem.”

“I don’t know where I put it.”

“Maybe it’s inside one of those cabinets,” Klaus said, but Eldritch grabbed another box and started rifling through it.

“You see, my friend and collaborator left me documents, coordinates, timelines, witness testimonies, and some of your letters, which give me an idea of who you are. Your story, if true, is remarkable.”

“Who is your friend again?”

“Helene Rossi,”

“I don’t think I know any Ellens.”

“It’s pronounced Helene. It’s French,” Klaus said.

“Is she your lover?”

“No. Why would you ask that?”

“There was an inflection in your voice when you said her name.”

“She passed away recently,” Klaus said.

“This death business seems to happen quite a lot,” Eldritch said.

“I was wondering if I could ask you some questions.”

“Are you going to record me?”

“Not if you don’t want to.”

“Who is going to see this?”

“This is merely a preliminary survey. I wanted to introduce myself and verify a few facts first.”

Eldritch pulled out something from the box. “Oh, look. A wallet.” He opened it and set it on the table. “Why have a wallet if you’re not going to put money in it, right?”

“Do you mind if I set up the camera?”

“Sure. What’s your name again?”

“Klaus Richter.”

“Richter, of course. I knew that.”

Klaus grabbed his camera and ensured the batteries were in working order. He set the tripod and ran a few tests while a gusty wind howled outside, propelling snow sheets in every direction. The wooden house creaked and groaned as it endured the relentless assault. He set a chair across from him, pointed the camera, and invited Eldritch to sit.

“Recording now,” Klaus said.

“I don’t feel any different,” Eldritch said.

“That’s good. Some people get nervous and start acting up when they’re in front of a camera,” Klaus said.

“I’m always me,” Eldritch said.

Klaus sat back and exhaled a visible cloud of vapor that dissipated into the chilly air. His face was flushed from his body’s attempt to preserve heat. “What could be so dangerous that you’d isolate yourself here, at the edge of the world?”

“I want to know what you know first,” Eldritch said.

Klaus flipped through his notes. “Is it true you are running away from a Draugr?”

“What is a Draugr?” Eldritch asked.

“It’s a being —a creature if you will— that can transport people to unending and unimaginable torment with a single touch.”

“I don’t think I've ever called it that.”

“Throughout the ages, different cultures have given it different names.”

“And that’s your story?”

“It sounds inconceivable, but that doesn’t mean you don’t believe in it.”

“What sort of torments are we talking about?”

Klaus selected some papers from his stack. “I have letters you wrote to your sister Banya describing how you failed to kill the Draugr and now fear it will hunt you down and take revenge.”

“Sure, but I don’t recall sharing with my sister any details regarding punishment.”

“According to Helene’s notes, your sister found others who experienced the creature’s touch.”

“She did?”

“Helene helped her. She was the best at finding people, things, information.”

“And these people, what do they say happens after the Draugr touches you?” Eldritch asked.

“After this creature touches you, you can spend years, if not decades, experiencing nothing but a variety of tortures in some subconscious dungeon inside your mind. Meanwhile, on Earth, in our timeline, only a second, a day, or a month passes. It depends.”

“Depends on what?”

“I don’t know. That aspect of Helene’s research is incomplete. My guess is that the Draugr also enjoys tormenting those who wait for the victim to awaken from the coma. Still, I ignore the criteria the Draugr uses to decide the amount of time that passes for us while the victim endures a disproportionately longer period of suffering.”

“So if this creature touches you, you suffer for, say, a year, and when you wake up, only a minute has elapsed on Earth?”

“This is the testimony of those who claim to have experienced this creature’s touch,” Klaus said.

“What do these people say about these torture scenarios?”

“Let me see. In one of them, the Draugr touches you, and you enter a viewing area where you watch the person you love the most through a glass. Your loved one sits on an electric chair, and your job is to save them by punching in a four-digit code. But you don’t know the code, so if you guess wrong, they get electrocuted. You need to punch in the code every minute, and the more you miss, the more the process gets botched, and the victim burns from the shocks.”

“What if I refuse to participate?”

“The guards enter and beat your loved one.”

“That’s it?” Eldritch asked.

“Well, the scenario repeats. It happens over and over for years and years.”

Eldritch laughed. “An electric chair! This Draugr creature could benefit from a more vivid imagination.”

“Another person reported being trapped in a suffocating chamber. The air was foul, a toxic brew that choked the lungs. Her survival hinged on a sinister pact: each breath demanded a piece of chocolate. She was forced to consume one chocolate to get one minute of oxygen. Eventually, the body rebels, so you either suffocate or shit and vomit your guts out.”

“I apologize for laughing,” Eldritch said.

“I have similar accounts from a dozen people who have never met and have nothing in common. I don’t know how to explain that,” Klaus said.

“I don’t mean to make fun of you. I just hadn’t cried from laughing in such a long time,” Eldritch said.

“There’s also the musical.”

Eldritch burst laughing. “A musical?”

“Picture yourself on stage, forced to sing and dance to the same show. If you make the smallest mistake, the show starts again from the beginning.”

“What happens when you finish the musical without errors?”

“A pride of lions chases you around the stage and eats you,” Klaus said.

Eldritch let out a roar of laughter. “Don’t tell me. And then the musical restarts?”

“This person lived the same scenario for one hundred and fifty years, according to Helene’s notes,” Klaus said.

“I think someone played a trick on you, my friend,” Eldritch said.

“It sounds childish, I must admit,” Klaus said.

“I haven’t been this entertained in ages. What else do your notes say? Do you have one more?” Eldritch said.

“Some scenarios are less obvious.” Klaus ran his fingers through his documents until he found it. “I was so immersed in this one, I felt as if I were physically part of it.”

“Finally, a good one!” Eldritch said.

“In this scenario, you’re in a very dark place.”

“Aren’t we all?” Eldritch said.

“It’s a valley that has been shrouded by darkness. The inhabitants are either lost in the gloom or have amnesia and amble aimlessly in this valley. Only one person, a wizard, remembers two things: that the valley used to be a vibrant place full of magic and that a person named Hantana is destined to restore the land to its past glory.”

“And you’re Hantana, I imagine,” Eldritch said.

“Whoever is trapped in this scenario is Hantana. In such case, you have to use your magic and clean the place from the thorns and boulders that block the passage to other biomes, where the valley’s residents are trapped,” Klaus said.

“That doesn’t sound so bad.”

“Then you must revitalize the valley by farming, mining, fishing, and foraging. You plant carrots and corn, fish for trout, collect stone, wood, and so on. The more tasks you complete, the more the other residents recover their memories and are happier. Part of your job is to build friendships with these villagers by visiting them often.”

“Are they terrible friends?”

“No, they’re lovely. But every time you complete a task, five more pop up. There’s this guy, Mike, who asks you to cook a cherry pie for a picnic, so you have to grow cherries and wheat, make a fire, find a way to bake the pie, and then when you have it ready and delicious, Mike asks you for milk —and where in the fuck are you going to find a cow?”

“Why does Mike need milk?”

“Because he wants to bring his girlfriend back from the darkness, and milk was her favorite drink. She loved pies and picnics, and Mike wants to jolt her memory because she doesn’t remember him.”

“So you help Mike, and what happens?”

“Then he wants you to change the wallpaper in his house to her favorite color. After, he wants you to build furniture so she can be comfortable when she returns from oblivion. But then there’s also Lila Loom, Roxy Radiant, Hugo Hoot, Captain Coralreef, Milo Puddlefoot, Tania Twinkles, Gus and Gertie Gadget, Nina Nightshade, Reginald Paws, Willow Whisp, Benny the Brave, and so on. You have to complete quests for them as well. And yes, you improve the valley, but the more you work, the more work there is. Everyone is always happy, so their gratitude means nothing. It’s like thinking that zero and one are close to each other, but then you start counting the numbers in between, and you never finish.”

“Why would anyone believe in such nonsense?”

“The hope that derives from believing you’re inching closer to bringing light to the valley is what truly shatters the spirit. But you keep doing favors for these villagers, and you work day and night because there’s nothing else to do,” Klaus said.

“I cannot believe that an accomplished filmmaker like yourself came all this way for this,” Eldritch said.

“You’re right. This is the stupidest thing I’ve ever done. I don’t know what I was thinking,” Klaus said.

“I have a theory.”

“What is it?”

“I think you’re the one who has been hiding,” Eldritch said.

Klaus felt a twinge of embarrassment. He was expecting something more profound and meaningful, but he traveled more than two thousand miles only to find himself relegated to playing the clown for a stranger. This man, Julian Eldritch, was just a lonely old fool like him —another failed story.

“I just remembered where it is!” Eldritch stood up and searched the cabinet.

“I don’t know why I believed Helene,” Klaus said. “It’s so unlike her to let me down so profoundly.”

“Helene had nothing to do with this,” Eldritch said.

“I know. It was my decision. I did it to myself,” Klaus said.

“Were you two in love?”

“She was married to my friend.”

“So what? Those things happen every day,” Eldritch said.

“Still.”

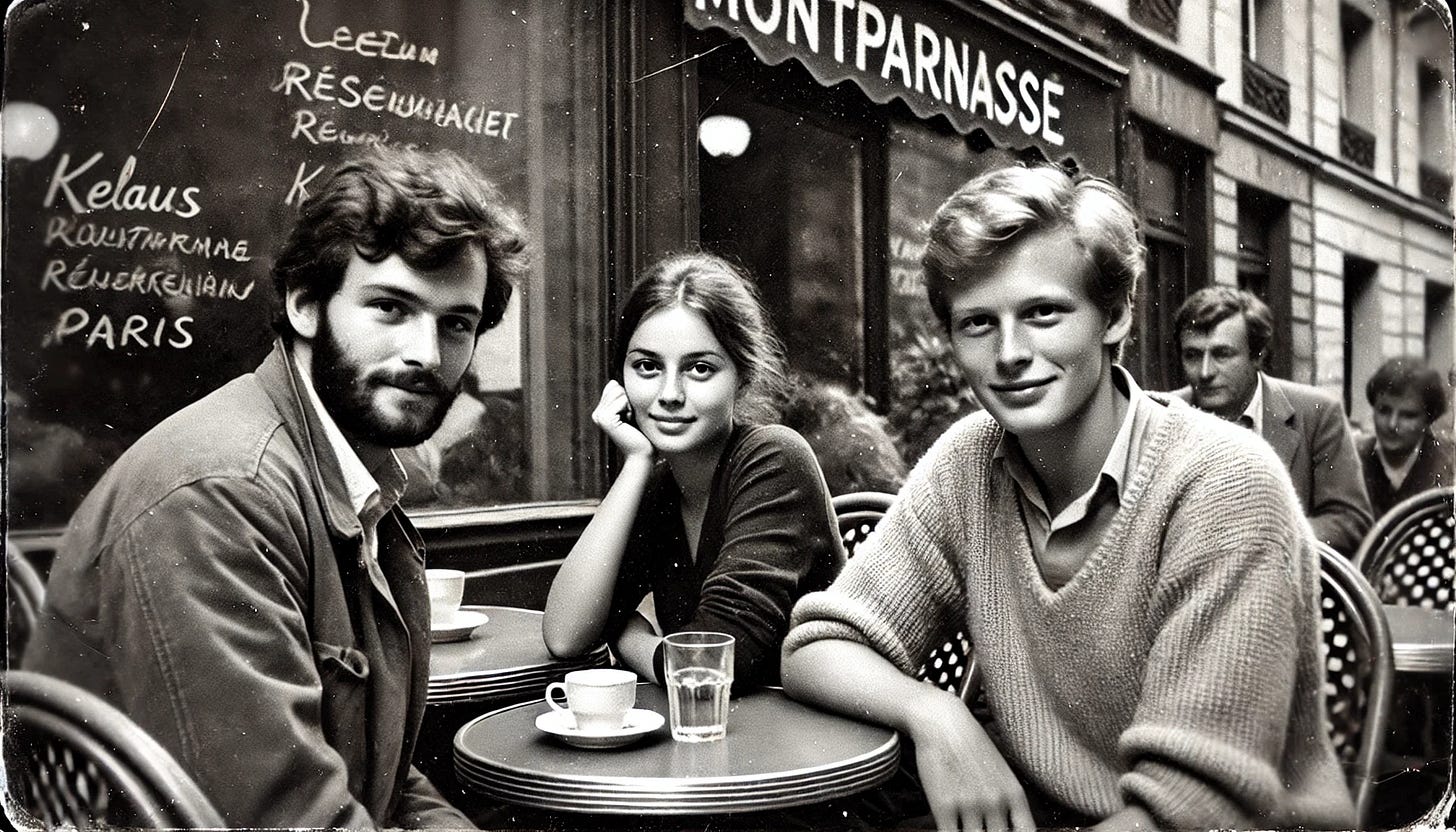

Eldritch found what he was looking for and showed it to Klaus: an old photo of Emil, Klaus, and Helene at a cafe in Paris. “I’m just trying to figure out what you did to Emil,” he said. “He could’ve traded for anyone, but he picked you.”

Klaus felt strange, as if the planet had tilted on its axis. The cabin light dimmed, and a heap of ice replaced the crackling fire in the chimney. He knew there was no point in opening the door.

“What happened to Julian Eldritch?” Klaus asked.

“Just know that my only job is to express an act of vengeance.” And at that moment, the creature gently touched Klaus’ hand.

Part IV

Helene opened her eyes and sat up. She surveyed the bedroom as if it was her first time there. Emil, his eyes heavy with worry but brightening upon seeing her awaken, grabbed her hand, but she withdrew it quickly.

“Who are you?” she asked.

“It’s me, my love. Emil. Your husband. I’m so happy you’re back.”

“Who are they?” She pointed at the crew with the cameras and microphones.

“I read your notes on the Draugr and found a way to bring you back. These people are here to help tell your story. I mean, it’s such an unbelievable tale. We must film it, I thought. How could we not?” Emil said.

She climbed out of bed on the far side, distancing herself from Emil, and exited the room. She searched the house and followed the light until she saw the glass door that led to the garden. Emil stood a few paces away, watching Helene with concern and confusion. The film crew followed closely without making a sound. The director made a few gestures, and the crew slinked around Helene. There she was, on her knees, digging a hole in the ground. Emil hesitated but then gradually approached.

“Helene, maybe you should rest. You’ve been through a lot and—” Emil said.

“Don’t touch me,” she said.

“Helene, I’m just trying to help you. You don’t need to be afraid of me,” Emil said.

“These carrots are not going to grow themselves,” she said.

“Let’s focus on the planting then. I won’t touch you, I promise. Do you need the seeds or perhaps some water?” Emil asked.

“I need to bake a carrot cake for Sammy, then fix the windows in Barry Beakbuster’s house, and after, I must collect wood and seashells for Oscar Owlwise.”

Emil gave Helene a reassuring smile before heading off. She watched him leave, then she resumed her digging. Sometime later, Emil returned with a small packet of carrot seeds and a watering can. By then, the garden was full of holes.

“Here you go. Everything you need,” he said, setting them down near her while keeping his distance.

Helene opened the packet and began to plant the seeds. Emil watched, his hands behind his back. He wanted to say something and make a connection but held back, respecting her space.

“I need to stop the darkness from returning,” she said.

Note from the author:

One of the punishments in “A Gentle Touch” was inspired by Dreamlight Valley, a Disney game my daughter is playing on Xbox. At first, I helped her with the reading, but as I watched her play, I sat beside her and assumed the role of strategic consultant: “No, no, no, don’t change your outfit again. Focus on gathering more wood right now. Turn back! We forgot to collect the raspberries!”

Much like the hellish scenario Klaus describes, in the game, the player must use “Dreamlight” magic to bring back villagers and restore their memories. The darkness, also known as the “Forgetting,” threatens to destroy the valley. The player must complete quests for the villagers because they can’t do a single thing for themselves.

Imagine this: Moana is trapped on an island, and you convince her to return to the valley. But first, you must collect eight pieces of wood and three silk yarns because she needs to fix her canoe. You do that and then pay the three thousand coins to release her (because “The Forgetting” is running a playbook from the Sicilian mafia.) And Moana is super happy, which means you are happy, too. But then a new quest pops up, and she won’t return until you build her a house (price: five thousand coins.) Okay, so you sell your kidney and several pints of blood and get the dough. And then she wants you to help Maui get back to the valley, and Maui needs to eat three meals made of ingredients you don’t have, which are found in areas of the game you have yet to unlock (price: twenty thousand coins to open each place.)

Just when you’re about to give up on the damn game altogether, you stumble upon the gem that frees Donald Duck, and all the other characters celebrate with fireworks and call you a hero. But Donald Duck wants you to build him a house, too. And a boat. And for that, you need special tools, which cost ten thousand coins.

I think of Dante Alighieri, who looks like a beginner next to the creators of Dreamlight Valley. Hell is actually a place full of hope. It’s a beautiful, sunny, colorful valley that constantly makes you feel disappointed and deflated but rewards you enough to suggest you’re getting closer to a transcendental milestone. After all, you’re a mere five thousand coins away from rescuing Elsa and Anna. And what else are you going to do? Quit? After all the raspberries you’ve harvested and all the fish you’ve cooked? Are you insane? You keep going.

Nice, slow vortex of a read. Milan Kundera meets Stephen King. Think I'll skip the melatonin gummy tonight, as my dreams often make a meal of whatever I thought about during the day.

This story is so riveting, I just couldn't stop reading. The game though, well that's another story. Thank you for sharing such great writing.